Introduction

Headaches affect approximately 50% of all people, and it is the most common pain condition worldwide. Primary headaches - migraine and tension - account for 50% of all headaches.1 With just migraines alone, a model-estimated percentage of employees with migraine headaches ranged from 14-19%, resulting in lost productivity and greater healthcare costs compared with the general population and costing American employers about $13 billion a year.2,3 In Europe and North America, most patients who experience migraine headaches have consulted a physician at some time because of their condition.4

Osteopathic manipulative treatment (OMT) has been a mainstay of osteopathic physician practices for many decades now, and over the years, literature has shown that these techniques have been a safe and effective treatment modality for many pain and musculoskeletal disorders.5–7 OMT is used to help correct structural imbalances, improve circulation, and relieve pain. Factors consistently associated with decreased OMT use in medical practice include lacking satisfactory OMT training in the postdoctoral years and being unprepared to integrate OMT into practice.8 For treating headaches specifically, the primary target of OMT would be the myodural bridge, with techniques such as suboccipital inhibition.

Although these techniques have been traditionally practiced by osteopathic physicians, given the recent osteopathic and allopathic accreditation merger, there has been growing interest among allopathic physicians to learn these practices.9–11 Ascension Providence Hospital’s Family Medicine Residency Program has Osteopathic Recognition, which is a “designation conferred by the ACGME’s [Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education’s] Osteopathic Recognition Committee upon ACGME-accredited programs that demonstrate, through a formal application process, the commitment to teaching and assessing Osteopathic Principles and Practice at the graduate medical education level.”12 Capable providers can give patients alternatives and adjuncts to pain medications and invasive procedures.

The Osteopathic Recognition Track Curriculum in our residency program has been developed over the course of several years. There is a “Team DO” track that all osteopathic residents and interested allopathic residents are a part of and meets once a month at Wednesday morning didactics. Attendance is often limited due to rotations at different sites, night shifts, or patient care duties. As such, it is difficult to standardize the “Team DO” experience. As part of the residency curriculum, there is a month of OMT rotation that is completed during the intern year as an osteopathic resident and during the second year as an allopathic resident. A brief educational headache OMT intervention was implemented to provide a much more standardized approach and experience. The objective of this pilot study was to determine the effect of this brief educational headache OMT intervention on the confidence and knowledge of headache OMT for allopathic and osteopathic physicians.

Materials and Methods

This was a cohort study that was approved by the Ascension Providence Hospital Institutional Review Board (IRB#1743603). Participants were Postgraduate Year 1 and 2 Family Medicine residents at Ascension Providence Hospital who had seen patients 18 years and older who were referred to the OMT clinic for headache or neck pain treatment. The patients seen did not include anyone with malignancy, fracture, and other contraindications to OMT. By completing the surveys, the residents gave their consent to participate in the study.

Both MD and DO residents participated in the study during their OMT rotations in the time frame August 2021 - June 2022. We had a prerecorded 20-minute lecture that was provided to residents at the beginning of their OMT rotation that detailed the basics of head and neck OMT diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment. For clarity, the brief educational intervention at the start of the OMT rotation month and the 20-minute video along with the pre and post surveys were the only additions to the current Osteopathic Recognition Track curriculum. An osteopathic family medicine attending physician was always present during all OMT sessions so that technique could be corrected in real time and for patient safety.

Demographic information was collected. Knowledge was measured through self-assessment by each resident participant before and after the brief educational intervention. The survey questions, including questions modified from Busey, et al. (2015), focused on the OMT didactic session on headache and neck pain and confidence in OMT headache and neck pain evaluation.13 Surveys were based on a Likert scale, measured using a scale of 1 to 5 (1=not at all and 5=most).

Due to the small sample size, a non-parametric test, Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test, was used to analyze the paired data. IBM SPSS Version 25 (IBM, Armonk, NY) was used to run the statistical analyses. Median and interquartile range (IQR) were also generated. Statistical significance was set at p value < 0.05.

Results

A total of 3 MD and 4 DO Family Medicine residents participated in the study. The prior OMT education and/or clinical experience differed among the residents: 4/7 (57%) reported significant experience (100+ hours), 1/7 (14%) had moderate experience (21-60 hours), and 2/7 (28%) reported minimal experience (5-20 hours).

Table 1 shows the survey median (IQR) scores pre and post educational intervention.

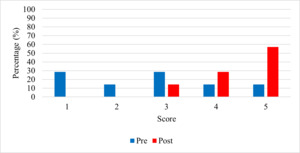

There was a statistically significant increase in comfort with OMT billing (p=0.041, Figure 1) and with completing an OMT visit within the allotted amount of time (p=0.025, Figure 2). No other survey items were statistically significant pre and post survey.

Figures 1 and 2 show the percentage of residents indicating their level of comfort based on billing and completing an OMT visit within the allotted amount of time, respectively. For these two measurements specifically, there was a median pre-score of 3 and median post-score of 5 and 4 for comfort with OMT billing and comfort with completing an OMT visit within the allotted amount of time, respectively. Of note, the lowest pre-scores for OMT billing were 1, 1, and 2, with the corresponding post-scores of 4, 5, and 4, respectively.

Discussion

This pilot study demonstrated that a brief educational intervention for allopathic and osteopathic residents in using OMT for headache treatment, a diagnosis that is routinely seen in family medicine practices, could provide valuable information on its effectiveness. Even though only two of our measurements in Table 1 were statistically significant, it is worth noting that the starting measurements for confidence in one’s OMT skills - using OMT routinely, recommending OMT, and interest in developing OMT skills - were already high with a score of 4 or 5 to begin with. This indicates that beyond this brief educational intervention, the overarching Osteopathic Recognition Track Curriculum has resulted in a group of residents confident in the OMT skills.

To our knowledge, very few studies have been previously reported concerning allopathic residents and their ability to learn OMT.10,11 Dubey et al. (2021) conducted an OMT elective over two years for allopathic residents and faculty.10 The study found statistically significant increase in knowledge and confidence in treating with OMT. The study found a directional increase, although not statistically significant, in the use of OMT post-curriculum.10 Another study on an OMT elective rotation for MDs indicated that after residency graduation, those who took the elective rotation had a higher comfort score in providing OMT care and referral to a DO provider, although not statistically significant, than a control group who did not take the elective rotation.11 These studies have somewhat different outcomes. Similar to our study, the results were mixed. Some outcomes were generally not statistically significant, although some were leaning in the direction of improvement.

With the merger between all allopathic and osteopathic residency programs in 2020, it became possible for interested allopathic residents to join all osteopathic residents in our Family Medicine residency program’s osteopathic recognition track. Our Osteopathic Recognition Track Curriculum included a month-long rotation in OMT, where residents were trained in both inpatient and outpatient settings to treat various regions and types of somatic and visceral complaints.

For two of our measurements, comfort with OMT billing and comfort with completing an OMT visit within the allotted amount of time, there was a statistically significant improvement, which was very reassuring considering our small sample size. There were other measurements that were not statistically significant, such as confidence in helping improve a patient’s pain and/or range of motion as well as how likely a resident sees themselves using OMT routinely. These were likely not statistically significant due to the small sample size. Other measurements, such as how likely residents were to recommend OMT clinic to non-OMT patients, how interested residents were in further developing their knowledge/skills, and how helpful residents found OMT lectures and hands-on sessions for developing their knowledge/skills, were also not statistically significant. However, this is likely because the pre-scores were very high to begin with.

The potential benefits of providing such a brief educational intervention could include improving headache symptom severity and duration, range of motion, and patient satisfaction, as well as decreasing likelihood for patients to return with similar complaints. OMT is a skill that can become another tool in the provider toolkit, in addition to prescribing medications, pain psychology, and physical therapy, and providers are more likely to utilize it as an attending if it is practiced and honed during residency.

According to the 2023 American Osteopathic Association’s Osteopathic Medical Profession Report, 11% of all physicians in the United States are osteopathic.14 Additionally, more than 25% of all medical students currently pursuing medicine are at osteopathic institutions.14 This increase could translate to an increase of the availability of OMT as a safe and practical tool for clinicians to utilize, both diagnostically and therapeutically. Providing this education during the formative years of residency to allopathic residents is an underutilized opportunity and providing it for osteopathic residents will increase the likelihood for it to be utilized in future practice.

Our study has limitations. The sample size was small, so generalizability is very limited. The study was also limited by coronavirus disease 2019 due to an inability to teach in group settings for didactic purposes and time constraints for data collection.

As for future directions, although it was a limited study due to the above reasons, we would like to see this study be replicated and/or expanded with different residency programs and with different body regions. We recommend that OMT education could be widely available to allopathic physicians for the head and neck. It can be explored further to other regions such as low back pain and any other areas that are amenable to be taught and practiced.

Conclusions

Overall, the results of this pilot study are promising. This study indicated an improvement in OMT billing and timely completion of an OMT visit by osteopathic and allopathic Family Medicine residents. As the sample size is very low, we recommend more studies on this topic.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Ascension Providence Family Medicine Residency Program and Research Department for their support of this project.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

CORRESPONDING AUTHOR

Eric P. Leikert, DO

Department of Family Medicine

Ascension Providence Hospital/Michigan State University College of Human Medicine

16001 West 9 Mile Road

Southfield, MI 48075

Phone: 248-849-3441

Email: eric.leikert@ascension.org