INTRODUCTION

Radiation safety education is an important aspect of any radiology department secondary to the potential negative health effects of radiation exposure. When performing fluoroscopy-guided procedures, which accounts for a large amount of radiation exposure in the medical setting, it is possible for the patient to be exposed to a significant amount of radiation.1,2 As a result, there is a potential risk for patients to experience both deterministic and stochastic side effects. Deterministic effects occur when a tissue receives radiation above a threshold dose and can result in predictable injuries (e.g., skin erythema), whereas stochastic effects (e.g., radiation-induced cancer) can occur at any dose, with the risk of development increasing proportionally with exposure.1–3

A key principle in the world of radiology is the phrase “as low as reasonably achievable”, or ALARA. In other words, when performing a diagnostic exam or interventional procedure that exposes a patient to ionizing radiation, one should aim to use as low a dose as is reasonably achievable in order to obtain a study or outcome that is of acceptable, diagnostic quality. Therefore, it is encouraged that fluoroscopy times be recorded and compared to established benchmarks in an ongoing effort to keep dose to both patient and provider to a minimum.4,5

Fluoroscopy time is the total time the X-ray source is on and actively emitting X-rays.2 Therefore, this is commonly used as a surrogate marker for patient radiation exposure. Previous studies have described average fluoroscopy times and doses for fluoroscopy-guided lumbar puncture (FGLP) at their respective home institutions.6–8 In addition, other studies have described methods of trending fluoroscopy time/radiation dose for neuroradiology fellows in order to assess the degree of competence in fluoroscopic procedures as an individual progresses through training.9,10 Many of these studies also specifically compared fluoroscopy times with variables such as provider experience level, patient age, and patient BMI. In general, it has been found that average fluoroscopy times increase with patient BMI and age and decrease with increasing provider experience, with some exceptions. While the authors are not aware of any published guidelines from the American College of Radiology (ACR) in regards to an acceptable dose for fluoroscopic lumbar puncture, general practice is to follow ALARA.

Our primary objective for this study was to determine the average radiation dose of lumbar punctures performed by providers in our radiology department across attendings, residents, and physician assistants. Our secondary objective was to determine the potential effects of demographic and clinical factors on radiation dose usage.

METHODS

This is a retrospective chart review approved by the Ascension Providence (now Henry Ford) IRB (IRB Study # 1830035-1). The electronic health record (EHR) was accessed in order to obtain information on the patient’s BMI and age at time of procedure. We included patients aged 18 or older who received a fluoroscopic lumbar puncture between 2016 and 2021 at either the Ascension Southfield or Novi campus. We excluded patients who did not have a complete data set in regards to age, BMI, radiation dose, proceduralist role, and date of procedure within the EHR/Picture Archiving and Communication System (PACS).

Procedure notes within the EHR/PACS were reviewed in order to obtain data on fluoroscopy time, dose (mGy), DAP (dose area product) (uGy-m2), proceduralist role, if the procedure was successful, and the date of the procedure. Fluoroscopy time was used as the primary surrogate measure of patient radiation exposure. The “dose” represents the cumulative air KERMA (Kinetic Energy Released per unit Mass) and reflects the energy delivered to a small volume of air at a standardized reference point assumed to be at the patient’s skin, not the actual absorbed dose in the patient’s tissues. DAP is the product of air KERMA by the irradiated field area, providing a better approximation of the total energy imparted to the patient. Both indices are valuable for relative comparisons but have important limitations: air KERMA does not account for backscatter or patient-specific absorption, and DAP does not directly translate to organ or effective dose. For residents specifically, data on the dates they were on Interventional Radiology (IR) rotation, number of lumbar punctures performed in their radiology career at the time of procedure, and the date the procedure was performed were collected. The timeframe for data collection was between 2017-2020 and employed convenience sampling.

Possible confounding factors included patient Body Mass Index (BMI) and age. The higher the BMI and age, the more difficult the procedure typically is.6,7,9,11 Increased difficulty in performing the procedure may increase the fluoroscopy time required. Quantitatively, we assessed if a significant difference exists between providers of different training levels (attendings, radiology residency year 1-4 [R1-4], mid-levels) and the degree of difference that may exist. In addition, we assessed the radiation dose change per number of lumbar punctures performed. We generated descriptive statistics such as means and frequencies. We performed inferential statistics such as ANOVA to compare groups and Pearson’s correlation to establish relationships between continuous variables. IBM SPSS Version 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) was used to analyze the data. Statistical significance was set at the 0.05% level.

RESULTS

A total of 370 patients who had lumbar punctures performed using fluoroscopy guidance were examined for this study. The mean age of these patients was 52.0 (SD = 16.9) years, and the average BMI was 31.3 (SD = 8.5). Regarding patient gender, 242 (65.4%) were female and the remaining 128 (34.6%) were male.

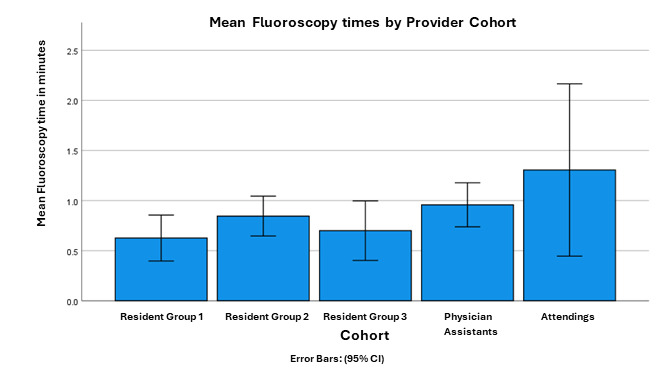

Fluoroscopy times were recorded for a total of 18 providers, eight (44.4%) of which were resident physicians, five (27.8%) were physician assistants (PAs), and the remaining five (27.8%) were attending physicians. Residents results were grouped by year, i.e., Resident Group 1, 2, and 3 contain Diagnostic Radiology Residents of different class years. More specifically, in this case Residents in Group 1 were approximately from the 2017-2018 class, Group 2 the 2018-2019 class, and Group 3 from the 2019-2020 class.

The total number of lumbar punctures performed across all provider cohorts, i.e., the combined total for all Residents, Physicians’ Assistants, and Attending Physicians, was 370. The average number of lumbar punctures performed across all providers was 21.56(SD =12.50). The range in number of lumbar punctures performed was from 1 – 44. Of the 370 lumbar punctures, 231 (62.4%) were performed by residents, 104 (28.1%) by PAs, and 35 (9.46%) by attending physicians.

In terms of sedation methods used, 317 (85.7%) lumbar punctures were performed using only local anesthetic, 28 (7.6%) were performed using moderate sedation (which typically involves administering intravenous fentanyl and midazolam), and 25 (6.8%) utilized general anesthesia. Average dose in mGy was 29.9 (SD = 89.2) with the lowest being a 0mGy dosage, and the highest being a dosage of 1,259mGy. The Average DAP (uGy-m2) was 332.4 (SD = 802.0), with a range of 4-8954uGy-m2. In addition, the average fluoroscopy time for all providers who performed fluoroscopy-guided LPs was 0.834 (SD = 1.33), with a range of <1 minute to 15.1 minutes.

Data patterns were then examined for possible associations between variables of interest. A regression line of best fit was plotted comparing fluoroscopy time and patient BMI. The line of best fit was Y = 0.49 + 0.01 * x. The slope = 0.01, therefore fluoroscopy times increase minimally at 0.01 per unit increase in BMI. A Pearson correlation was also performed, r (368) = 0.074, p = 0.156, the results of which suggest a very small, but non-statistically significant association between fluoroscopy time and patient weight.

Similarly, a regression line of best fit was plotted comparing fluoroscopy time and patient age. The line of best fit was Y = 0.19 + 0.01 * x. The slope = 0.01, therefore fluoroscopy times again increase minimally by 0.01 per unit increase in age. A Pearson correlation was also performed, r (368) = 0.155, p < 0.01, the results of which suggest a small, yet statistically significant association between fluoroscopy time and patient BMI.

Next, average fluoroscopy times were compared by sedation method used. More specifically, Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) procedures were used to compare the average fluoroscopy times for patients who had lumbar punctures performed using only local anesthetic (L), with moderate sedation (M), or under general anesthesia (G). The majority of lumbar puncture performed, 317 (85.7%), used local anesthetic, while 28 (7.57%) used moderate sedation, and the remaining 25 (6.76%) utilized general anesthesia. Homogeneity of variances were accessed by Levene’s test for equality of variances (p = 0.72), meaning that the variances are approximately equal. Mean fluoroscopy times across the three sedation methods were as follows: Local anesthetic = 0.826 minutes (SD = 1.36), moderate sedation = 0.79 minutes (SD = 0.709), and general anesthesia = 0.98 minutes (SD = 1.51). Average fluoroscopy times across sedation methods were not significantly different, as assessed by a one-way ANOVA test, F (2,366) = 0.17, p = 0.84. (Figure 1)

When examining for possible associations between the independent (i.e., age, patient weight) and dependent variables (i.e., fluoroscopy time), a statistically significant small (i.e., < 0.3) positive correlation was observed between age and fluoroscopy time, r (368) = 0.16, p < 0.01. Put another way, age explained 2.56% of the variability in fluoroscopy time. Similarly, a statistically significant small negative correlation was observed between age and patient weight, r (368) = -0.28, p < 0.01. In this case, approximately 7.84% of the variability in patient weight is explained by patient age.

Mean fluoroscopy times increased along with the “experience” level of providers. The mean fluoroscopy times for the 3 resident groups combined was 0.707 minutes (SD = 1.13). For each of the three resident groups, the mean fluoroscopy times were: 0.626 minutes (SD = 1.09) for the first group of residents, 0.846 minutes (SD = 0.75) for the second group of residents, and 0.700 minutes (SD = 1.361) for the third group of residents. For the PA’s, the average fluoroscopy time was higher with 0.958 minutes (SD = 1.125). Finally, the attending physicians had the longest average fluoroscopy times with an average of 1.306 minutes (SD = 2.504). Levene’s test was not statistically significant with a p = 0.103, meaning that variances were equal. However, ANOVA results were not statistically significant, meaning that there was not a statistically significant difference in the mean fluoroscopy time across cohorts, F (4, 364) = 2.123, p = 0.07. We also wanted to examine the final ten lumbar puncture procedures performed by residents during their residency training. Based on the last ten attempts recorded for the 8 residents assessed in this study, the average fluoroscopy time was 0.43 minutes (SD = 0.41). (Figure 2)

Finally, one of the primary questions this study was designed to examine was whether the number of lumbar punctures performed was correlated with a decrease in average fluoroscopy time. Recall that the authors hypothesized that less time per procedure would be observed the more experienced a given provider was in using fluoroscopy-guided technique. A linear regression model was run examining the standardized fluoroscopy time (dependent variable) with the number of lumbar punctures performed (independent variable). An R = 0.185 was observed, indicating a small correlation, along with an R squared = 0.034. In other words, this suggests that 3.4% of the variance in standardized fluoroscopy time could be explained by the number of lumbar punctures performed. Similarly, an adjusted R squared of 0.029 was observed, suggesting that, more realistically, 2.9% of the variance in fluoroscopy time may be able to be explained by the number of lumbar punctures performed. More specifically, there was an approximately 0.009 minute decrease in the standardized fluoroscopy time for every lumbar puncture performed. While this 0.009 minute decrease is small, this relationship was statistically significant, p = 0.02. Further, this translates to a formula that can be applied to this data to determine the degree of fluoroscopy time decrease we would expect as the number of lumbar puncture procedures performed increases.

This formula is: 0.981 + (-0.009 x number of lumbar punctures performed).

For example, from this we can compute the following possible predicted decreases in the average fluoroscopy time we would expect:

-

1 lumbar procedure = 0.973 minutes (95% CI: 0.830 – 1.116)

-

5 lumbar procedures = 0.939 minutes (95% CI: 0.818 – 1.059)

-

10 procedures = 0.896 minutes (95% CI: 0.800 – 0.992)

-

20 procedures = 0.810 minutes (95% CI: 0.734 – 0.887)

-

30 procedures = 0.725 minutes (95% CI: 0.615 – 0.834)

-

40 procedures = 0.639 minutes (95% CI: 0.472 – 0.806)

-

44 procedures = 0.585 minutes (95% CI: 0.391 - 0.793)

NOTE: As the relationship is linear, the increase in the number of lumbar punctures is limited to the range of lumbar punctures recorded in this study, i.e., from 1-44.

These numbers suggest that while the decrease in fluoroscopy time is relatively small, at a decrease of just 0.009 minutes per lumbar puncture performed, that the additive value of the summary decrease may be worth exploring further in future studies. In addition, future studies, with larger data sets and greater specificity, may be able to identify a “point of diminishing returns” that could further assist in establishing benchmarks for trainees.

DISCUSSION

Our study aimed to assess the radiation dose delivered to patients during fluoroscopy-guided lumbar punctures that were performed by different healthcare providers in our radiology department, including resident physicians, attending physicians, and physician assistants. More specifically, how fluoroscopy time changed following subsequent procedures performed, and how these average times varied between different provider cohorts. Additionally, we observed how fluoroscopy times may be affected by secondary variables such as the patient’s age, patient body mass index, or means of sedation while performing the procedure.

The primary outcome of our study showed that every lumbar puncture a provider performed was associated with an average decrease in fluoroscopy time by 0.009 minutes. However, while statistically significantly different, p = 0.02, only 2.9 - 3.4% of the variance in fluoroscopy times appears to be explained by the number of lumbar procedures performed. It would perhaps be interesting to have this study replicated in other clinical environments. If these results are replicated, then perhaps further clarity can be ascertained as to what other factors might contribute to possible decreases in fluoroscopy time, and thus, less radiation exposure to patients.

In addition, with such data, the possibility to extrapolate the expected average fluoroscopy time, and therefore expected radiation dose delivered, for each fluoroscopy-guided lumbar puncture performed by a provider, may be attainable. This has potential, for example, to be utilized by radiology residency programs in setting benchmarks for residents as they advance through their training to reach certain levels of proficiency. Interestingly, no statistically significant difference in average fluoroscopy time was observed between residents, attendings, or PAs. This observation in particular was unexpected; however, important points for further investigation that were not included as a part of this study were success rates in LPs performed between cohorts, the number of attempts per procedure, or whether or not a procedure performed by a resident or PA required assistance/intervention from an attending physician. It is also worth considering that attending physicians are more likely to be involved in technically difficult or failed cases. These challenging scenarios may require additional imaging for accurate needle placement, which could artificially increase fluoroscopy times for attendings despite their greater expertise. The large standard deviation for attending fluoroscopy times in our study (SD = 2.504) supports this possibility. Without a prospective or standardized assignment of cases to control for case complexity, this effect is difficult to quantify. These variables are considered to likely be the greatest limitations of this study and should be considered in subsequent studies.

Regarding our secondary variables, we found that the average length in fluoroscopy time, and necessarily, radiation dose, increased significantly as a patient’s age increased, as had been demonstrated in previous studies.7,9,11 This is postulated to be secondary to expected senescent changes, increased intervertebral disc degeneration, and resultant osteophyte formation limiting the number and size of viable anatomic windows for lumbar puncture success.12–16 Other factors such as prior spinal surgery, spinal hardware, or possibly other comorbidities or physical factors are considered that may have had an impact on difficulty in successfully performing a lumbar puncture, thus increasing the time and radiation for said procedure.

Patient BMI and the means of sedation administered to patients, on the other hand, were not shown to significantly impact the average fluoroscopy time during lumbar punctures performed by our providers. It was initially hypothesized that as BMI increases, average fluoroscopy time may also increase. Anecdotally, it is often found that performing a fluoroscopy-guided lumbar puncture on an individual with a higher BMI is more difficult, due to a combination of a greater amount of soft tissue necessary to traverse prior to achieving appropriate terminal needle placement, a proportionally longer needle being more difficult to direct, and an association with increased degenerative changes.6,7,9,11,17 This is thought to possibly necessitate a greater number of needle repositionings and a more accurate initial trajectory, though no significant difference in radiation dose was observed in this study. Additionally, no significant difference in mean fluoroscopy time was observed when compared with means of sedation. Of note, the vast majority of lumbar punctures performed (n=317, 85.7%) simply utilized local anesthetic without any need for sedation, while only 28 and 25 patients received moderate sedation and general anesthesia, respectively. With that being said, observing data with a larger sample size for procedures performed with moderate sedation or general anesthesia may well demonstrate differing results from this initial study or further support data already obtained.

For example, individuals that had received forms of sedation may receive a lower average radiation dose if fewer attempts/needle adjustments were needed, thus requiring fewer fluoroscopic images, secondary to patient relaxation. Alternatively, increased radiation dose in patients receiving moderate sedation could reasonably be hypothesized as patient cooperation may be limited. There are times when small adjustments in patient positioning are needed to optimize access and the ability for a patient to cooperate may be hindered with sedation. Those under general anesthesia, while not able to actively cooperate themselves, can still be repositioned by providers and staff.

An additional limitation to consider is a limited pool of providers whose data was available for study. While the number of attending physicians and physician assistants in our department are much less likely to fluctuate, observing data over a longer period of time with newer, more senior, and even graduated resident physicians as they matriculate and depart from our program may provide a broader insight and greater power when ascertaining fluoroscopy time trends. Other potential limitations not directly accounted for include patient positioning (i.e. prone vs. lateral decubitus) and needle length, though the latter is indirectly considered in relation to BMI as needle length is typically proportional.

While performing fluoroscopy-guided procedures, such as lumbar punctures, it is important to keep radiation dose to the minimum amount necessary for both the patient and provider’s overall safety. Previous studies have described average radiation doses for fluoroscopic lumbar puncture at their respective home institutions, though, to our knowledge, no standard guidelines through the ACR are available describing acceptable radiation doses or fluoroscopy times for fluoroscopy-guided LPs.6–8 We compared average fluoroscopy times for LPs performed between various provider cohorts in our institution, extrapolated projected decreases in average fluoroscopy time with subsequent experience, and compared these data to secondary variables, including patient age, BMI, and means of sedation during procedures. While further investigation is likely necessary, a formula obtained through our data may be of use to aid in describing possible guidelines and expectations in attaining a certain level of proficiency for resident physicians, physician assistants, and attending physicians alike.

CONCLUSIONS

Information obtained during this project can help us better understand our providers’ average radiation dose for lumbar puncture compared to previously published values while also evaluating several independent variables and their influence on fluoroscopy time. Using these comparisons, we may be able to identify groups who have radiation doses higher than the published average and who may benefit from an educational program focused on decreasing radiation dose in fluoroscopy. Data regarding changes in radiation dose over time for resident physicians may help delineate an ideal time in a resident’s training to provide an educational program on radiation safety as well as laying out guidelines and expectations for proficiency. It is our hope that the results of this study may serve to guide other future research on this topic, ideally allowing for further efficiencies in advances towards reducing radiation dose for fluoroscopy-guided lumbar puncture and patient exposure to radiation.

CREDIT Roles

Jacob Babb: writing – original draft, writing – review & editing

Alex Kaechele: conceptualization, writing – original draft

Eric Rinker: conceptualization, writing – original draft

Sam Wisniewski: methodology, formal analysis, writing-original draft, writing -reviewing and editing

Grace Brannan: methodology, writing-review and editing