Introduction

The Milestones framework for assessment of Internal Medicine resident competency was proposed by the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medicine Education (ACGME) in 19991 and implemented in 2013.2 After implementation, residency program directors identified concerns related to the number of milestones within each competency, difficulty understanding the milestone language, and lack of consistency across competencies.3 In response, the ACGME created a committee to review and develop new program requirements. Internal Medicine Milestones 2.0 was developed and implemented in July 2021.4 Among the six ACGME competencies—Medical Knowledge, Patient Care, Practice-based Learning, System-based Practice, Interpersonal Communication, and Professionalism–three specific sub-competencies were created in professionalism. These included Professionalism 1: Professional Behavior and Ethical Principles, Professionalism 2: Accountability, Professionalism 3: Well-Being and Resiliency.5 Similarly, the ACGME’s Clinical Learning Environment Review Program 2.0 highlights the importance of professionalism and its impact on the quality and safety of patient care.6 Program Directors on the Internal Medicine committee of the Southeast Michigan Center for Medical Education (SEMCME), a large regional consortium of medical educators, expressed concern implementing and assessing professionalism. The primary aim of our study was to review the present status of professionalism education among Internal Medicine residency programs.

Methods

The Southeast Michigan Center for Medical Education (SEMCME) is one of the largest community-based medical education consortiums in the United States.7 Seventeen member institutions with separate residencies and residency curricula collaborate to solve common residency problems. One problem identified by the Internal Medicine committee was how professionalism was taught and assessed in Internal Medicine residency training programs in Southeast Michigan. To address this gap, the committee developed and implemented a survey.

The committee convened a group of educators with experience in survey methodology and program assessment to develop a survey instrument. After review of the literature on professionalism,8,9 six focus areas were identified: 1) determine how Internal Medicine residencies in Southeast Michigan teach and assess professionalism in their programs; 2) measure faculty and resident perception of professionalism in their institutions; 3) identify barriers to evaluating professionalism; 4) identify types of professionalism lapses observed in their institution and how they are reported; 5) describe how program recognize and reward positive professional behaviors, and 6) determine resident and faculty rank of professionalism compared to other competencies.

A preliminary survey instrument was developed by the group to assess the study’s specific aims. Using the Delphi technique,10 the group reached a consensus on the survey questions. The survey was piloted for usability, and questions were refined. The final survey consists of 17 multiple-choice questions, one question requiring ranking of priorities, and 7 questions about demographic data. Our survey is available in the appendix. Residents from participating sites were notified of the survey by e-mail. Participation was voluntary.

IRB approval was obtained at each participating institution. All data were blinded. Trinity and Ascension data were held by a webmaster at Trinity Oakland. Data from the Detroit Medical Center were held by the affiliated University web master. For analysis, chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were performed utilizing SPSS version 28 software. Significance was defined as a p-value of less than 0.05. The multicenter study was approved by the IRB at Trinity Health Oakland. IRB # 2023 – 004.

Results

Four Internal medicine and one Med / Peds program from four teaching hospitals participated in the study. Each hospital obtained IRB approval. A total of 240 resident and 37 faculty surveys were sent. 85 residents and 33 faculty responded. Of respondents, 55.1% identified as male, 39.0% as female, and 5.9% declined to identify. 26.3% self-identified as white, 31.3% as Asian/ South Asian, 8.5% as African American / Black, and 13.6% as Middle Eastern. 20.3% declined to self-identify their race. Due to the small sample size, PGY – 1, -2, and -3 resident responses were pooled. Similarly, core faculty, associate program directors’, and program directors’ responses were pooled. During the survey period, one program was transitioning program directors (PD), resulting in six PDs for five programs. Both identified as PD on the survey, resulting 6 PDs for five programs.

Teaching and assessing professionalism

When asked if their program had a written professionalism curriculum, 77.6% of resident respondents, but only 39.4% of faculty reported having a professionalism curriculum (p<0.001). None of the six program directors reported having a written professionalism curriculum.

When describing how professionalism is taught, 77.6% of residents and 60.6% of faculty listed lectures, 37.6% of residents’ vs 24.2% of faculty listed OSCE’s, 48.2% of residents vs 27.3% of faculty reported on-line assignments, 31.7% of resident vs 36.4% of faculty reported small group discussion, 18.8% of resident vs 9.1% of faculty listed assigned reading and 14.1% of residents’ vs 18.2% of faculty reported role play and methods to teach professionalism. No significant differences were reported between residents and faculty on how professionalism is taught.

Evaluation of professionalism

Of all respondents, the most common method reported was end-of-month evaluation 83.1%, followed by incident report submission 56.8%, self-reflection 56.8%, non-physician (360 degree) evaluation 45.6%, OSCE 36.4% and role play 11.9%. Curbside nurse or faculty evaluation was 22.9% and 27.1%, respectively. Only OSCE demonstrated a significant p value between residents 42.4% and faculty 21.2% (p = 0.04).

Recognition and rewarding positive behavior

Only 62.4% of residents and 69.7% of faculty (p=0.52) reported their program always / most of the time / usually recognized and rewarded positive behavior. When asked how does your program reward professional behavior, 56% of residents and 52% of faculty responded annually recognition, 26% of residents and 71.4% of faculty reported receiving / sending e-mails. End-of-month recognition was reported by 28% of residents and 14.3% of faculty. Other reported rewards reported were gifts and recognition on social media. (p = NS).

Perception of professionalism

When asked if their sponsoring institution promotes a culture of professionalism that supports patient safety and personal responsibility, 82.4% of residents and 63.6% of faculty strongly agreed or agreed (p=0.05). When asked if faculty and staff physicians are exemplary role models for residents, 80.0% of residents and 72.7% of faculty responded always / most of the time / usually. 20.0% of residents and 27.2% of faculty felt that faculty and staff physicians were never or only sometimes exemplary role models. (p = 0.46).

When reported by cohort, self-identified females felt faculty were always / most of the time / usually exemplary role models 87.0% compared to self-identified males 86.2% (p=1.0). Whites reported 83.8% always / most of the time / usually compared to non-whites 92.1% (p=0.29). (Table 1).

Confidence and barriers in evaluating professionalism

Only 28.2% of residents and 36.4% of faculty felt very confident evaluating professionalism (p = 0.68). When asked to identify barriers to evaluation, 41.2% of residents and 24.2% of faculty reported no barriers (p = 0.09). Ten-point six percent of residents and 42.4% of faculty cited lack of training as a barrier (p < 0.001). Fourteen-point one percent of residents and 33.3% of faculty reported a lack of appropriate evaluation tools (p = 0.04), and 7.1% of residents and 30.3% of faculty reported being uncomfortable with providing professionalism feedback (p= 0.002). Forty-two point four percent of residents and 42.4% of faculty reported a lack of time as a barrier (p = 1.0) (Table 2).

Professionalism lapses

Participants were asked to report if they had observed any breaches in professionalism exhibited by themselves, their peers, or faculty. Faculty and resident differed in their responses. Twenty-seven-point one percent of residents and 9.1% of faculty reported no observed professionalism lapses (p = 0.05). Faculty observed more incidence of copy and paste (22.3% vs 48.5% p = 0.01); tardiness (32.9% vs 67.7% p = 0.002); inability to accept feedback (23.5% vs 51.5% p = 0.004); incomplete records (16.5% vs 48.5% p = <0.001); not completing evaluations on time (14.1% vs 33.3% p = 0.04); and missed assignments (21.2% vs 33.3% p = 0.23). (Table 3).

Ranking of competencies

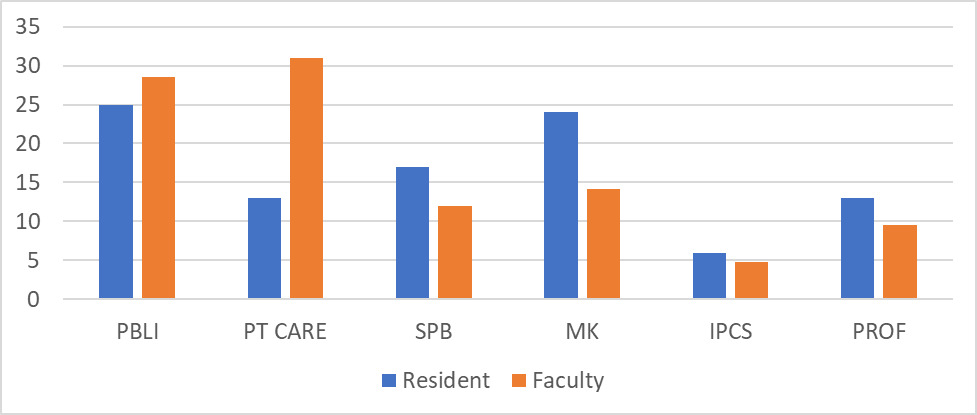

Residents and faculty were asked to rank the six competencies as they are prioritized within their residency program. Competencies were listed per ACGME parlance with no further explanation. Faculty felt patient care was the most important competency. Residents felt Practice-Based Learning and Improvement and Medical Knowledge were most important. Both ranked interpersonal and communication skills least important and professionalism second least important competency. (Fig. 1).

Discussion

The ACGME revised and implemented milestones 2.0 and CLER 2.0.4–6 The SEMCME Internal Medicine Program Directors expressed difficulty understanding or implementing the required changes in their program, especially with regards to professionalism. To determine the present status of professionalism education, a questionnaire was developed measuring how programs teach and assess professionalisms, how residents and faculty perceive professionalism, how programs reward positive professional behavior, how residents and faculty ranked professionalism compared to other competencies, and identify barriers to evaluating professionalism lapses in their institution.

More residents than faculty felt the program had a “professionalism” curriculum. No Program director reported a professionalism curriculum. This may be due to both residents and faculty concluding that the multiple teaching and evaluation modalities of professionalism in their programs constituted a curriculum. A written curriculum provides a standard (Performance Dimension) by which faculty promote and evaluate professionalism. Programs should develop a professionalism curriculum, disseminate the curriculum among faculty and residents, and provide education on evaluating and mentoring professionalism.

The most common teaching method was lecture followed by OSCE, small group discussion and on-line learning. The most common evaluation tool was end-of-month evaluations, incident reports, non-physician evaluation (360 evaluation) and self-reflection. The most common source of an incident report was a formal complaint to the Program Director or to the administration. Curbside faculty, nurse or peer reports were not common sources of an incident report. Perhaps minor professionalism breaches are not recognized, are ignored, or are perceived as insignificant enough to be reported. Only major professionalism breaches, generating a report to the Program Director or Administration, are deemed necessary.

Only 62.4% of residents and 69.7% of faculty feel positive professional behavior is rewarded always, most of the time, or usually. Despite the emphasis on this competency by ACGME, programs do not appear to praise and promote professionalism. Despite increased emphasis by ACGME on teamwork, both residents and faculty ranked Professionalism fifth and Interpersonal and Communication skills the least important of the six competencies, reflecting physicians low perceived value of these skills (Fig 1). Residents ranked Medical Knowledge as most important while faculty ranked Patient Care as most important. This may reflect residents versus faculty goals for training. Residents need to “pass the boards,” get a job or fellowship, complete research, and work on their visa. Faculty focus on patient care needs.

Second, residents are not as observant of professionalism breaches compared to faculty. This is reflected in resident (27.1%) versus faculty (9.1%) in reporting no observed professionalism breaches. Previous studies reported similar differences between faculty and medical students.9 Faculty reported observing more professionalism lapses, including copy and paste, tardiness, inability to accept feedback, incomplete records and missed assignments, than residents. Perhaps residents had fewer opportunities to observe these behaviors during a three-year residency. Second, residents may not perceive these breaches as significant and impacting their training goals. This dichotomy may explain faculty reporting difficulty in providing feedback.

Similarly, 82.4% of residents but only 63.6% of faculty felt their sponsoring institution promoted a culture of professionalism. We suspect residents are isolated from “hospital politics” while faculty are privier to conflicts and policies within their institutions. Second, residency is three years. Faculty have been on staff longer and have more opportunities to observe aberrant behaviors.

When asked if faculty were exemplary role models for residents, most residents and faculty reported always, most of the time, or usually. However, 20.0% or residents and 27.2% of faculty felt staff physicians were never or only sometimes exemplary role models. Having one of five faculty be inappropriate role models for residents is disturbing. When reported by cohort, self-reported females felt faculty were always / most of the time / usually exemplary role models 87.0% compared to self-reported males 86.2% (p=1.0). Our results differ from previous studies demonstrating gender differences in evaluating professionalism.11 Whites reported 83.8% always / most of the time / usually compared to non-whites 92.1% (p=0.29). (Table 1).

Similarly, 41.2% of residents but only 24.2% of faculty reported no barriers evaluating professionalism. Only 10.6% of residents, but 42.4% of faculty, felt they required additional training in evaluating Professionalism despite available resources. Fourteen-point one percent of residents but 33.3% of faculty felt they lacked the tools to evaluate professionalism. The perceived lack of evaluation tools and faculty confidence may be a consequence of professionalism ranked the second least important competency. (Fig 1). Programs need to provide additional training. Only 2.4% of residents, but 12.1% of faculty, felt there were financial barriers. These responses may reflect residents focusing on training and not being privy to hospital budgets and politics.

The strengths of our study are five participating residency programs (four Internal Medicine and one Med-Peds) from four participating institutions in three different health care systems. Weaknesses include using an unvalidated survey, a low resident response rate, and a limited faculty sample size. PG – 1, – 2, and – 3 residents’ answers were batched to improve power. Resident perceptions of professionalism may change as their training progresses. Senior resident responses may align more with faculty perceptions. Finally, several questions were open-ended, allowing participants to interpret terms themselves. For example, “financial barriers” and “ACGME competency” were not defined.

In summary, Internal Medicine residents and faculty vary in their perception of professionalism. Both felt Interpersonal and Communication Skills and Professionalism were the least important of the six competencies. Faculty feel that additional training in evaluating professionalism and providing feedback is needed. Both faculty and residents feel that approximately one in five faculty were never or only sometimes exemplary role models. Lack of professionalism affects the clinical learning environment, physician wellbeing, and quality of care. Our study suggests additional training for residents and faculty, highlighting the importance of professionalism in quality of care and the clinical learning environment. Follow-up studies should reevaluate resident and faculty attitudes and quality metrics.