DESCRIPTION OF THE CLINICAL CASE

The patient was an 87-year-old woman with past medical history significant for uncontrolled type 2 diabetes mellitus (on long term insulin therapy), depression, hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and gradual weight loss from ageusia/gastroparesis. The patient was seen at her primary care provider’s office with concern for memory loss. The patient’s medication list included amlodipine (5 mg daily), atorvastatin (40 mg daily), benazepril (40 mg daily), insulin detemir (10 U daily), metformin (1000 mg twice a day), metoprolol tartrate (37.5 mg daily), and omeprazole (20 mg daily). She took two over-the-counter supplements daily – a multivitamin and vitamin D supplement. She was not taking any other over-the-counter medications.

A Montreal Cognitive Assessment Test (MoCA) evaluation was performed, and the patient scored 13/30, consistent with moderate cognitive impairment. MoCA is a brief cognitive screening tool for mild cognitive impairment and is copyrighted. Under this copyright, MoCA may be used without permission by qualified clinicians. Approximately 2 years earlier, the patient had a Saint Louis University Mental Status examination performed at her Medicare annual wellness visit and scored 22, consistent with a mild neurocognitive disorder. Of note, the patient had a known history of depression, which was stable at the time of the current visit, but the patient was not in therapy and was not currently taking medications for depression. One month prior to the current visit, at her Medicare annual wellness visit, the patient’s Patient Health Questionnaire-2 score was 0. Approximately 6 months before the current visit, her Patient Health Questionnaire-9 score was 5, consistent with mild depression. Bloodwork collected at the current visit was unremarkable. The patient was prescribed donepezil (5 mg daily) during the current visit for the treatment of dementia.

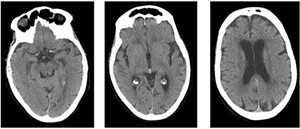

Two days after starting donepezil, the patient presented to the emergency department due to visual hallucinations, which included seeing her deceased husband’s face superimposed on her current husband’s body. On evaluation, her vitals were stable. Laboratory testing (Table 1) was notable for hyperglycemia (glucose = 374 mg/dL), as well as acute kidney injury (creatinine = 1.4 mg/dL, baseline around 1.0 mg/dL), but was otherwise unremarkable. Urinalysis was not consistent with a urinary tract infection (Table 2). Head computed tomography was obtained, which was negative for acute processes, but showed chronic small vessel changes (Figure 1). The patient was treated with insulin and intravenous fluids before being discharged home, without any changes to her home medications.

Five days after her emergency department visit, the hallucinations were not improved, and the patient was again seen by her primary care provider. Patient reported ongoing visual hallucinations, including seeing a fan “swinging sideways”, a dog sitting in a chair, and a pink rabbit going up the wall.

WHAT IS YOUR NEXT COURSE OF ACTION?

-

Admit the patient for altered mental status due to uncontrolled hyperglycemia.

-

Stop the donepezil.

-

Add an antipsychotic medication for treatment of worsening of dementia with associated psychosis.

CORRECT ANSWER: #2, Stop the donepezil.

This case shows a temporal relationship between the initiation of donepezil and the onset of hallucinations. Of note, this patient had an extensive evaluation, both outpatient and in the emergency department, to exclude other etiologies (infection, electrolyte abnormality, stroke) for her symptoms.

There are few case reports documenting hallucinations secondary to donepezil; more common side effects reported include gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, dermatologic, and neurologic side-effects such as extrapyramidal symptoms.1,2 However, pharmacovigilance databases report a 3% risk of hallucinations with acetylcholinesterase inhibitors.1 It is hypothesized that when patients with preserved cholinergic function receive acetylcholine stimulation this can contribute to arousal and deficits in cognitive performance.

Alternative etiologies for new hallucinations were considered, including Lewy body dementia (LBD). Of note, a complete evaluation for LBD was not conducted. The patient demonstrated several core clinical features of LBD; specifically, fluctuating cognition and recurrent visual hallucinations that are well formed and detailed. Additionally, she demonstrated several supportive clinical features including hallucinations, delusions, and anxiety/depression. However, she did not demonstrate the motor features of parkinsonism (bradykinesia, rest tremor, rigidity) and did not have a known rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder. Additionally, the patient did not have a known history of falls, syncope, autonomic dysfunction, hypersomnia, or hyposmia. Further testing for biomarkers could have been considered to help clarify this diagnosis. However, the patient did not undergo testing for indicative biomarkers at this time (single-photon emission computer tomography or positron emission tomography scan, iodine-metaiodobenzylguanidine myocardial scintigraphy, polysomnography, or electroencephalogram testing). The partial evaluation of LBD as the underlying etiology of the patient’s symptoms is one of the limitations of this case.

INCORRECT ANSWERS

-

# 1, Admit the patient for altered mental status due to uncontrolled hyperglycemia. Although the patient presented to the emergency department with hyperglycemia and dehydration, her hallucinations failed to resolve after treatment with fluid and insulin. Additionally, the patient had chronically uncontrolled type 2 diabetes, with hyperglycemia, without any prior episodes of hallucinations.

-

# 3, Add an antipsychotic medication for treatment of worsening of dementia with associated psychosis. Behavioral and psychiatric symptoms of dementia can be challenging to manage for family and caregivers. While antipsychotics may be used off-label in severe or refractory cases, non-pharmacologic treatments (minimizing physical and emotional stressors, routine formation, environmental modification) comprise the first line treatments.3 Additionally, prescribers should be cautious with the use of antipsychotics in dementia, and should regularly reassess their benefits versus risks, given to the potential for adverse events – including an increased risk of death.4

DISCUSSION

The strength of this case rests in the fact that a thorough evaluation for organic etiologies was conducted, through both imaging and laboratory studies. This case report also shows a clear temporal relationship, with the onset of hallucinations 48 hours after starting the medication. Our case highlights an underreported adverse effect of donepezil-induced hallucinations, emphasizing the importance of recognizing and managing such side effects in dementia patients. This report underscores the need for vigilant monitoring and timely intervention in elderly patients initiated on cholinesterase inhibitors. One major limitation of this case report is the lack of a complete assessment for LBD. The patient demonstrated several core and supportive clinical features of LBD. Biomarker testing including single-photon emission computer tomography/positron emission tomography scan, myocardial scintigraphy, polysomnography, and electroencephalogram could have helped to clarify this diagnostic question.

PATIENT OUTCOME

After reviewing the patient’s results from the emergency department, no clear organic etiology of the hallucinations was identified. The worsening of dementia, with associated psychosis, was entertained as a possible etiology. However, given the timing of symptom onset with initiation of donepezil, the decision was made to hold donepezil. After holding donepezil, all hallucinations resolved within 72 hours and did not reoccur. While LBD was not fully ruled out as an etiology of patient’s hallucinations, the prompt temporality of symptom onset with medication initiation and discontinuation of symptoms with medication discontinuation, make medication side effect a more likely etiology of the patient’s symptoms. The patient was referred to Neurology for further evaluation of memory changes. Neurology recommended further testing including electroencephalogram, neuropsychiatric and cognitive testing, and brain imaging. This case highlights the importance of considering side effects of medication in the elderly population when they experience changes in mental status.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to acknowledge the patient from this case report and her husband, who graciously allowed us to write this case report in the hope that others could learn from this experience.

FUNDING

The authors have no funding to report for this study.

DISCLOSURES

The authors have no disclosures or conflicts of interest to report for this study.

CORRESPONDING AUTHOR

Lauren Groskaufmanis, MD, MPH

Department of Family Medicine

Henry Ford Health Providence Hospital

16001 W Nine Mile Rd

Southfield, MI 48075

Phone: (248) 437-1744

Email: lgroskal@hfhs.org

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS:

Conceptualization: Lauren Groskaufmanis (Lead), Ioana Stan (Supporting). Writing – review & editing: Lauren Groskaufmanis (Supporting), Madison S Meyer (Supporting). Writing – original draft: Ioana Stan (Lead).