INTRODUCTION

Summer camp courses offered by academic institutions to encourage young people to pursue specific professions are common and are used to enhance educational and career planning not only in medicine but also in science, technology, engineering, and math professions.1–5 Since at least 1987, medical schools have been utilizing summer programs/camps to encourage young people to consider healthcare as a career.6

In 2001, our hospital began offering a summer program as an opportunity to enrich the education of high school and undergraduate college students and to prepare them for the journey into healthcare and research-related careers. The summer program has hosted between 25 and 35 participants each year over a two- to four-week period and has educated more than 500 students over the last 20+ years. Even though the program began as a healthcare research-related course, during the last 10 years the program (Summer Program in Healthcare) has evolved into a daily system-based presentation by academic medicine faculty from a multitude of disciplines, lectures by second- and third-year medical students, cadaveric labs overseen by anatomists, simulated skills, some laboratory exercises, clinical experiences, and a group research project. In addition, the participants attended talks and workshops on the medical school application process, personal statements, and medical school interview tips. Even though the program has been in existence for over 20 years, previously only anecdotal outcomes have been recorded. Therefore, we evaluated the impact of the program on the students by assessing their matriculation into a healthcare profession or educational track.

METHODS

This was a retrospective study using data collected as part of normal assessment of programs conducted at Henry Ford Providence Hospital (formerly Ascension Providence Hospital) during high school and college summer breaks. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained (IRB RMI20230235). The period from 2015 to 2019 was chosen for two reasons. First, the authors found that some of the contact information collected as a part of the application process prior to 2015 was incomplete, corresponding to a shift in program management. Second, the 2020 and 2021 courses were canceled due to the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, thus creating a natural break as well as preventing the introduction of potential confounders.

To assess their career and educational choices, we surveyed students who attended the program by emailing a link to a 10-item Google Forms document twice between January and May 2023. Program application information was used as a source of email addresses. However, some of the learners either did not respond to or had changed email addresses since their cohort’s completion. It was discussed and determined that social media might be a pathway to contact previous participants where contact through email was returned. It was determined that LinkedIn® would serve as the primary source because the posted profiles skewed heavily toward academics and business. Following identification of persons on the site, an intra-site message containing a link to the anonymous survey was delivered first in June 2023. Follow-up messages were sent to those who did not respond in June of 2023. In situations where cohort members could not be identified, attempts were made to locate a profile on other platforms, i.e., Instagram ®, Facebook®, etc., and the process was repeated.

Survey items collected data on employment/education status, career goals, and attendance and graduation data, but no identifying or demographic data were collected (Appendix A).

The curriculum was based on the anatomy lectures, didactic lectures by nursing, specialty physicians, residents, and medical students. Additional exposure to the laboratory and imaging were provided. Hands-on experience in the anatomy lab and simulation lab were provided. Additionally, the learners participated in a team-based learning activity in which the learners were assigned to groups, chose a topic, completed a literature review, then presented the topic to the group. Learners were expected to have enough knowledge beyond the presentation to be able to field rudimentary questions. Written feedback was provided by their fellow students and the program faculty. A schedule of the typical week is shown in Appendix B.

Data were stored on a secure, firewall-protected, hospital Google Drive, and the data were only accessible by the authors. Descriptive statistics and frequencies were computed.

Because associated costs are an important factor related to the development and administration of programs such as these, available financial data were collected for each year, categorized, and descriptive statistics calculated. Physician and non-physician speakers volunteered their time. In-kind costs were computed for each group using $120.00 per hour for physicians and $50.00 per hour for non-physicians. Total financial costs were calculated by obtaining financial statements for three years and averaging the cost for every year, including supply costs and payments for lectures.

RESULTS

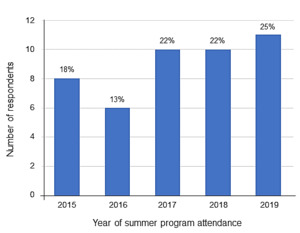

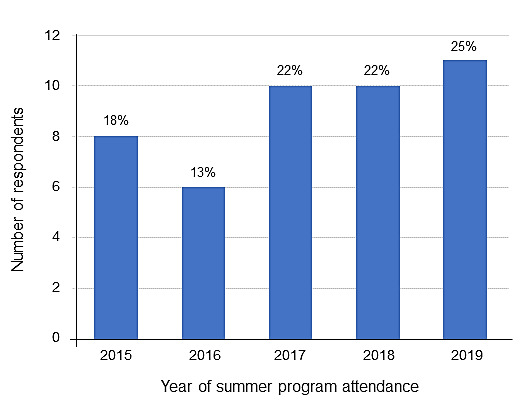

A total of 115 learners were sent the 10-item survey. Forty-nine surveys were returned, but 4 were incomplete, resulting in a response rate of 38% (45/115). Between 6 and 11 students from each year responded to the survey (Figure 1).

The purpose of the program was the encouragement of participants to seek careers in healthcare; therefore, three categories of data were collected from the students: 1) career goals, 2) educational attainment and employment status, and 3) the role the course played in their career and/or educational pathway. As might be expected, a large majority (73%) listed their career goal as healthcare. Other respondents’ goals included science (6.7%), engineering (4.4%), and other (8.8%), which included pilot, healthcare consulting, journalism, and public service (Table 1).

When asked about their current educational and/or work status, over half of all respondents (n=28) indicated they were still completing their education as either full-time students or working while continuing to attend school (Table 2). The remainder indicated they were working part- or full-time (n=17). Within the ongoing education subset, 23 respondents indicated that they continued to be full-time students who were either working part-time or not at all. Almost all of the working respondents, n=16 (94%), were working full-time. Finally, 35 (78%) of the respondents endorsed that they were either working and/or student in a healthcare-related field; most of them were either currently completing medical school (n=17) or were working in healthcare (n=12, Table 2).

Table 3 shows matriculation and educational attainment of the respondents. Most, n=42 (93%), affirmed that they had completed a four-year degree at the time of the survey. A total of 12 (27%) respondents stated they had completed a post baccalaureate program, 8 students (18%) from graduate programs, and 4 students (9%) from medical school. Additionally, 4 (9%) respondents endorsed participation in or completion of a fellowship or residency.

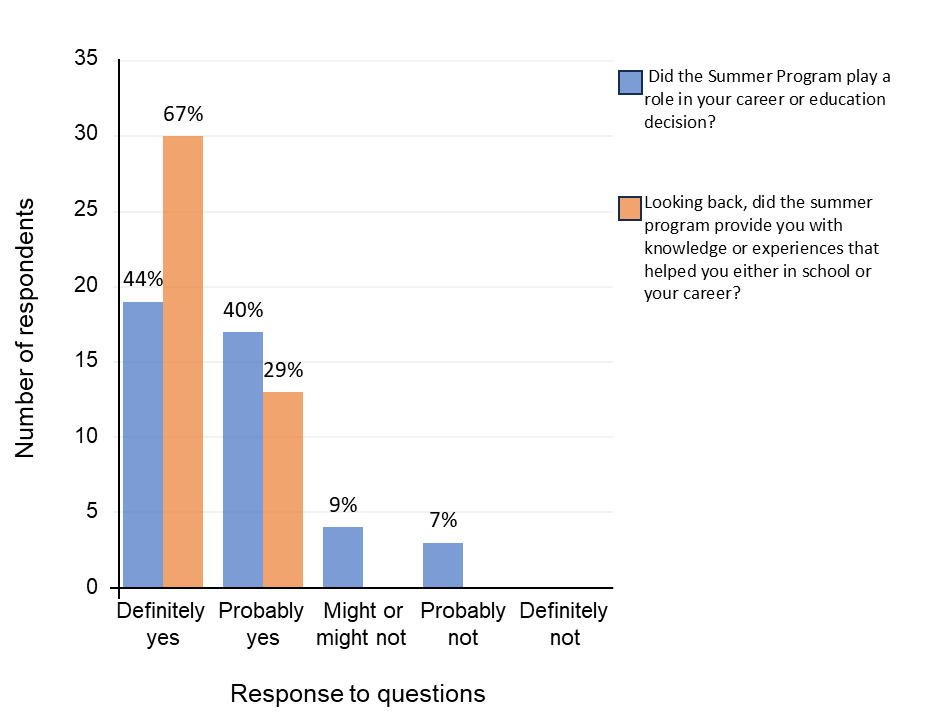

Two survey questions were asked to gauge the perceived impact of the program. Impact was measured using a five-point rating scale ranging from “Definitely Yes” to “Definitely Not”. The questions were:

-

Did the Summer Program play a role in your career or education decision?

-

Looking back, did the Summer Program provide you with knowledge or experiences that helped you either in school or your career?

A total of 36 (84%) respondents stated that the program either “definitely” or “probably” played a role in their career or educational decision. Almost all respondents, n=43 (96%), reported that either “definitely” or “probably” the Summer Program provided them with experiences that helped them in their education or career (Figure 2).

Lastly, the learners were polled about learner satisfaction related to the program. Nearly all learners, n=41 (96%), rated the program as excellent or good on a five-point scale.

To determine the cost to run the program, we computed our expenses in various categories (Table 4). The non-personnel-related costs averaged about $3700 per year. Most of the costs were for instructors and lecturers, as shown in Table 5. Each medical student instructor received a stipend of $3500.00 per course; depending on the length of the course, either 2 or 3 instructors were needed, resulting in a mean cost of $8167 per year. Practicing physicians and other persons delivering content were not paid, but the mean in-kind cost of physician instruction per year was $1520, and the mean for non-physicians was $217. Overall, the mean cost to run the program was $13,976 per year. When the number of students and length of the program was taken into consideration, the average cost per student per day was $30.51 (range $27.24 - $35.44).

DISCUSSION

The duration of healthcare-related summer programs cited in the literature varied from 1 to 30 days with different curricula (for example, introduction to the field, exposure to healthcare) with most courses ranging from 2 to 4 weeks.

The Summer Program in Healthcare is one of many pipeline programs held across the United States each year in different institutions. These programs are not specific to any one discipline, and they can be found in various areas of interest: biomedical sciences, medicine, pharmacy, and non-specific programming.1,7–14 Even though the areas of interest differed, there was significant cross-over in curricular activities. Most programs, including our program, provided opportunities for learners to meet and interact with physicians and/or other members of the healthcare community and to obtain guidance on college and specialty school admissions. Two programs included information on financial literacy as well as the more typical topics associated with healthcare programs.1,15 Additionally, four programs provided experiences in the clinical environment through shadowing physicians and healthcare workers.8,12,13,15

The data from the respondents showed that the Summer Program in Healthcare impacted the career and educational decisions of its participants. Most of the respondents have continued to post-secondary education and many have completed a four-year degree. Additionally, the respondents indicated that the program either provided resources that directly aided their decision regarding the field they chose or provided knowledge or skills that aided in their educational pathway. Because this was a program concentrating on healthcare-related materials, it was most interesting to note that of the 14 respondents that chose fields outside of healthcare, the program still influenced their decision. This could indicate that the program may have provided enough insight into healthcare to ensure that participants who were “on-the-fence” may have chosen alternative and possibly more personally appropriate pathways. While other programs investigated matriculation, our program broke matriculation down further by incorporating employment. While some of the respondents endorsed the traditional educational pathway from high school to college followed by medical/graduate school, many of the respondents indicated non-traditional pathways to education that included full-time employment.

There has been a wealth of evidence identifying pre-college factors related to college success.16–19 Similar to the Summer Program in Healthcare, all of the cited programs used a combination of experiential learning, exposure to physicians and other healthcare providers, basic-skills education, and mentoring. As compared to other programs, our program stands out by including the development of a research project completed and presented to the group at course conclusion.

Program differentiation occurred with respect to content based on what we have defined as “preparation for success properties”.1,9,15,20,21 Preparation for success properties included topics such financial literacy, test taking, and academic preparation. Since its inception, preparation for success has been considered a key component of our curriculum. The reporting by 96% that the course influenced their career decision, and by 73.3% that they chose healthcare as a career shows that the program met its goal.

The overall cost of the program for the three years in which all financial data was available, $41,928.75, was not insignificant to our department. However, the cost per student per day, $31, was not exorbitant. By comparison, only one source cited, Fritz et al., documented cost at $205.88 per student per day.9

The previous studies cited were prospective in nature. Learners were often selected based on their academic and socioeconomic standing. Stephenson-Hunter et al.,15 Fritz et al.,9 and Yeldora et al.21 selected high academically-achieving subjects representing underrepresented minorities. Winkleby et al.20 went to lengths to discuss matching groups based on academic level, gender, and ethnicity, but did not specifically comment on representation except that learners were from a “low-income family,” although applications from underrepresented groups were given priority. In contrast, our program did not screen applicants’ grades or socioeconomic factors prior to application and enrollment. However, it was assumed that many of its participants are academically prepared since applications were distributed through current healthcare workers within Henry Ford Providence Hospital.

The primary limitation of this study, due in large part to the low rate of return, was non-response bias. Attempts to identify students through social media were largely unsuccessful. Demographic data were not collected as a part of the survey, which may have allowed a comparison of the respondents to the non-respondents.

CONCLUSIONS

We found four studies with longitudinal outcome data; however, our study appears unique.1,9,15,20 By utilizing previous records and searching on social media, we were able to examine the progress of former students toward their career goals, not simply matriculating into a representative major. The evidence indicates that this program appears to have been successful in impacting its participants. Not only have these learners matriculated into healthcare and non-healthcare related fields based on their experience, but some of the previous learners are also now actively participating as active members of the healthcare community.

In conclusion, the data from the respondents showed that the Summer Program in Healthcare likely impacted its participants. Nearly all the responding graduates have matriculated into a college or university, and many continued into healthcare-related tracks. Moreover, the positive endorsement of items related to obtaining resources necessary for success provides evidence that the Summer Program in Healthcare achieved its goal. The Summer Program has been beneficial to high-school and undergraduate students in educating them about their career options at an affordable and reasonable cost to the institution to overcome the shortages in all fields of healthcare.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: Vijay Mittal (Lead), Jeffrey Flynn (Supporting). Methodology: Joseph Crutcher (Lead), Jeffrey Flynn and Vijay Mittal (Supporting). Validation: Joseph Crutcher (Lead), Jeffrey Flynn (Supporting). Formal Analysis: Joseph Crutcher (Lead), Jeffrey Flynn and Vijay Mittal (Supporting). Investigation: Hana Kallabat (Lead), Joseph Crutcher (Supporting). Resources: Joseph Crutcher (Lead). Data Curation: Joseph Crutcher (Lead). Writing-original draft: Joseph Crutcher (Lead). Writing-review and editing: Vijay Mittal (Lead), Jeffrey Flynn and Joseph Crutcher (Supporting). Visualization: Joseph Crutcher (Lead), Jeffrey Flynn (Supporting). Supervision: Vijay Mittal (Lead), Jeffrey Flynn (Supporting). Project Administration: Joseph Crutcher (Lead), Jeffrey Flynn (Supporting).

CORRESPONDING AUTHOR

Joseph L. Crutcher, DHS

Department of Medical Education

Henry Ford Providence Hospital

16001 West Nine Mile Road

Southfield, MI 48075

Phone: 248-849-7901

Email: jcrutch2@hfhs.org

FUNDING

The authors have no funding to report for this study.

DISCLOSURES

The authors have no disclosures or conflicts of interest to report for this study.