DESCRIPTION OF THE CLINICAL CASE

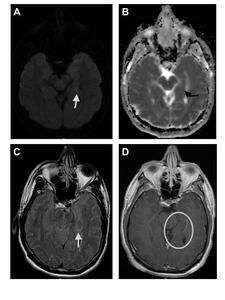

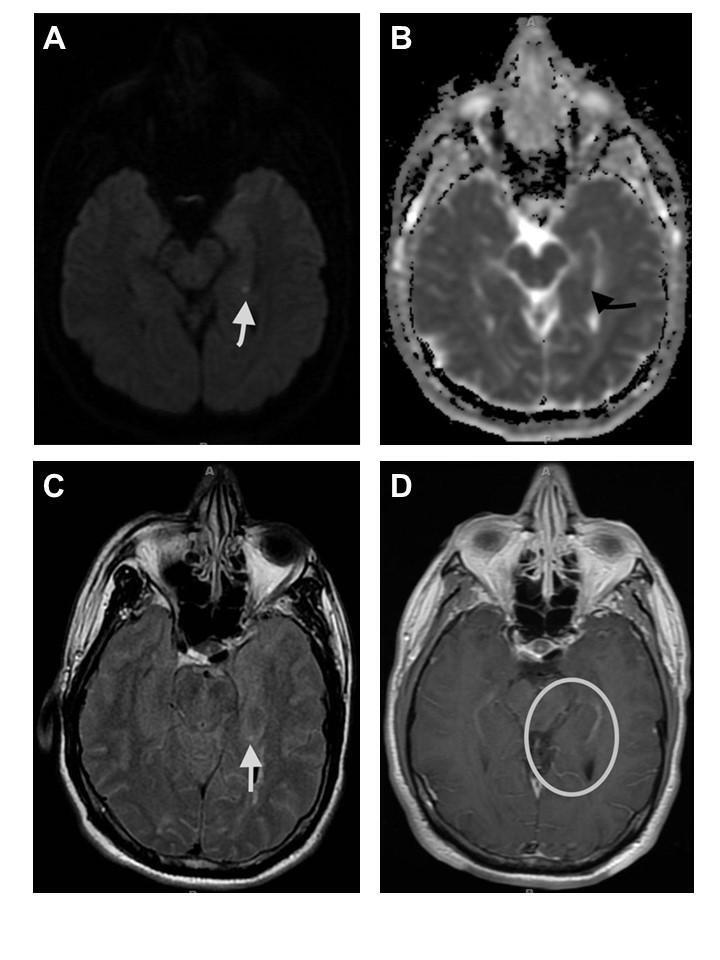

A 59-year-old male presented with an acute onset of confusion and an inability to recall events that persisted for 24 hours. He also described a frontal headache, heightened anxiety, and confirmed that he had not experienced similar episodes in the past. Notably, he was a regular marijuana user and a former tobacco smoker. His neurological examination was largely unremarkable, but he demonstrated a 0/3 delayed recall and displayed an anxious affect. Diagnostic tests revealed a positive urine toxicology screen for cannabinoids. A brain computed tomography scan indicated no acute hemorrhage, while the electroencephalogram showed no epileptiform focus or abnormal discharges. A transthoracic echocardiogram revealed an ejection fraction of 60-65% without regional motion abnormalities or shunt lesions. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain, with and without contrast, identified a small focus of restricted diffusion in the mesial left temporal lobe (see Figure 1).

WHAT IS YOUR NEXT COURSE OF ACTION?

Given the MRI findings, what clinical presentation is most probable?

-

Seizure

-

Amnesia

-

Confabulation

-

Right upper extremity weakness

CORRECT ANSWER: #2, Amnesia

Transient global amnesia (TGA) is a rare benign dysfunction of anterograde and immediate retrograde memory that can last up to 24 hours, with no other neurologic deficits.1 Although the exact cause of TGA remains elusive, it is hypothesized that migraines and vascular factors might be implicated.2 There is no specific laboratory test that confirms TGA. A set of diagnostic guidelines for TGA, suggested by Hodges and Warlow,3 encompasses:

-

Witnessed amnesic episodes.

-

Recorded anterograde amnesia during the episodes.

-

No change in consciousness or personality changes, only symptoms of amnesia.

-

Absence of other focal neurological signs.

-

No seizure manifestations.

-

Episodes limited to a 24-hour duration.

-

No recent head trauma or existing epilepsy.

INCORRECT ANSWERS

-

# 1, Seizure. Transient epileptic amnesia (TEA) is a form of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy in which patients experience recurrent, brief (under one hour) episodes of anterograde amnesia, often occurring upon waking. TEA typically involves recurrent amnesias, and while seizure episodes usually respond to treatment, interictal memory impairments generally persist. Although electroencephalograms for TEA patients commonly show abnormal temporal lobe discharges, our patient exhibited a non-recurrent pattern and had an electroencephalogram devoid of epileptiform abnormalities.2

-

# 3, Confabulation. Alcohol amnestic disorders (AADs), which encompass Korsakoff’s syndrome and Wernicke encephalopathy (WE), commonly manifest in individuals with a history of alcohol abuse. Korsakoff’s syndrome emerges as a residual syndrome in those who have experienced WE but did not receive timely and appropriate thiamine replacement. Both conditions can lead to anterograde and retrograde amnesia, with AAD also often causing executive dysfunction. On MRI, AAD-associated abnormalities can be detected, especially in WE, where changes in the periventricular white matter, medial thalami, mammillary bodies, hypothalamus, and tectal plate are observed. Specifically, WE typically showcases decreased T1 and increased T2 signals in these regions, alongside restricted diffusion. Given our patient’s absence of both alcohol abuse history and executive dysfunction, these diagnoses seem improbable.2

-

# 4, Right upper extremity weakness. Transient ischemic attacks or strokes usually present with focal neurological deficits, but isolated amnesia can be a rare manifestation. About 1.2% of cases presumed to be TGA might actually be ischemic amnesia. The presence of vascular risk factors or other neurological abnormalities could increase the likelihood of an ischemic event.2

DISCUSSION

Imaging features

Brain MRI can be normal or show findings of punctate hippocampal lesion on diffusion-weighted sequence on MRI. A retrospective observational research study noted that 70.6% of patients with TGA had hippocampal lesions on diffusion-weighted imaging, with an average of 1.05 lesions and an average lesion dimension of 4.01 mm.4 Studies have found that timing of MRI is important in the likelihood of detection. While lesions can be detected up to several days following symptom onset, they may only be detectable at least 12 or more hours following onset of symptoms. The lesions typically demonstrate a mild reduction apparent diffusion coefficient and are most commonly unilateral.4,5

In contrast with ischemic stroke, diffusion-weighted imaging shows hyperintensities and significant apparent diffusion coefficient reductions within minutes to hours, with persistent changes evolving over days to weeks and chronic alterations visible for months. TGA lesions are localized and temporary, while ischemic stroke lesions are more extensive and permanent, requiring urgent intervention. It is crucial to note that the primary role of MRI in this context is to exclude other potential diagnoses, such as tumors, encephalitis, or large infarcts.4

Prognosis

Most TGA patients require no specific treatment. The priority lies in ruling out other potential differential diagnoses and ensuring patient reassurance. Hospital observation is recommended until the amnesia resolves. The long-term outlook is generally favorable, with no heightened risk for mortality, epilepsy, cognitive decline, or stroke post-TGA episode. However, a minority (approximately 5.4%) may experience TGA recurrence, and some studies indicate possible subclinical memory function impairment persisting beyond one-year post-TGA.6

PATIENT OUTCOME

The patient was discharged in stable condition with his functions returned to baseline. We recommended routine cardiovascular and neurological assessments, given his history and imaging findings. Patient education on symptom recognition was advised. Additionally, addressing the psychological impact of TGA and offering appropriate counseling was recommended for holistic care.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Seti Belay (Equal), Mathew N Chakko (Equal). Writing – original draft: Seti Belay (Lead), Adithya Bala (Supporting). Writing – review & editing: Seti Belay (Equal). Validation: Seti Belay (Equal), Adithya Bala (Supporting), Mathew N Chakko (Equal). Formal Analysis: Seti Belay (Equal), Mathew N Chakko (Equal). Investigation: Seti Belay (Equal), Adithya Bala (Supporting), Mathew N Chakko (Equal). Data curation: Seti Belay (Equal), Mathew N Chakko (Equal). Resources: Seti Belay (Equal), Mathew N Chakko (Equal). Supervision: Mathew N Chakko (Lead). Project administration: Mathew N Chakko (Lead).

CORRESPONDING AUTHOR

Mathew N. Chakko, MD

Department of Radiology

Ascension Providence Hospital

16001 West 9 Mile Road

Southfield, MI 48075

Phone: 248-849-6170

Email: mathew.chakko@ascension.org