INTRODUCTION

Quality, as defined by the National Academy of Medicine, is the degree to which health services for individuals/populations increase the likelihood of a desired outcome and are consistent with current professional knowledge using the Plan-Do-Study-Act model.1 Therefore, quality improvement (QI) is the framework used to systematically improve care by providing patient-centered, effective, efficient, timely and safe care. Efforts by hospitals to improve quality are reflected at the institutional level by several publicly available assessments of hospital performance measures, including the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems2 and the Leapfrog Hospital Safety Grade.3

Change can be difficult, but it can occur with QI and patient safety (PS) education and development of all the institution’s healthcare staff, including trainees. Various systematic reviews have been published documenting effective educational methods for clinicians and trainees, but while learners have demonstrated improved knowledge, there has been limited success in this knowledge translating into improvements in quality or patient safety.4,5

Although the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) had been emphasizing resident and fellow training in practice improvement for several years, a greater emphasis on QI and PS training occurred with the implementation of the Next Accreditation System in 2013.6 One of many changes supporting the evolution of training was the Clinical Learning Environment Review, which was designed to provide feedback to healthcare institutions for how “to improve how clinical sites engage resident and fellow physicians in learning to provide safe, high quality patient care”.7 This emphasis on QI and PS training and involvement was further emphasized with the 2017 ACGME Common Program Requirements8 and continued to increase with the 2023 Requirements.9

As part of the Next Accreditation System, the ACGME implemented six core competencies: Patient Care, Medical Knowledge, Professionalism, Interpersonal and Communication Skills, Practice-based Learning and Improvement and System-based Practice.9 These 6 competencies are directly related to the quality and safety of patient care. The new QI and PS requirements fall under the Practice-based Learning and Improvement competency. Residents must receive training and experience in QI processes, including an understanding of healthcare disparities.9 Residents must also have the opportunity to participate in interprofessional QI activities.9 Defining the best methods to accomplish this training is the subject of much research. Since most publications have evaluated features of trainee QI and PS training at the program level, the purpose of our study was to determine how different institutions across the United States educate and integrate QI and PS training, including the event reporting system (ERS) utilization, into medical education in compliance with ACGME requirements.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data were obtained via a Google Forms survey accompanied by an implied consent form that was emailed to the Designated Institutional Officials (DIOs) of 650 United States’ ACGME-accredited institutions in September 2021; a second reminder was emailed in November 2021. DIOs were given 6 months to complete the survey. The list of the institutions was obtained from the ACGME website. The survey consisted of 34 multiple choice questions and utilized the Likert scale. The survey consisted of five main categories to obtain information regarding: institutional demographics, QI/PS training methods, ERS utilization, assessment and processing of ERS, and education provided. Although the survey was sent to all DIOs, only responders with at least one training program were included in the final analysis. The Ascension Providence Hospital Institutional review board reviewed and approved this study (IRBNET #1806880). Descriptives statistics were calculated.

RESULTS

Of the 650 emails sent, more than half (n=392) were undeliverable, leaving only 258 possible responders. Fifty-one responses were received from DIOs, and all but one met the inclusion criteria of having at least one training program, which translated to a response rate of 19% (=50/257). As shown in Figure 1, demographic results showed that most of the institutions had ≤500 beds (68%, Figure 1A) and ≤5000 workers (76%, Figure 1B) within their hospital. Institutions had 1-3 (26%), 4-20 (38%) or >20 (36%) graduate medical education (GME) programs (Figure 1C); most had <10 residency (64%) or fellowship (62%) programs (Figure 1D). Finally, all but one institution (98%, n=49) reported that they had medical students, but six of the 49 institutions did not allow medical students to use the ERS.

This survey found that while 90% of institutions (n=45) had an institutional QI/PS Committee, only 30% (n=15) of these institutions also had a GME-specific QI/PS Committee as well. Most institutions provided QI (88%) or PS training (94%), but only 71% and 83%, respectively, had mandatory training. The most common training methods utilized were online modules and lectures (Figure 2A). When DIOs were asked what educational programs their graduate medical education departments provided, most departments provided programs in communication (81%), feedback (80%) and other areas (Figure 2B). To see if differences in hospital Leapfrog Safety grades were related to various elements of the training methods, we examined each group of hospitals based on their safety grades. However, no significant differences were noted in the training and/or educational programs offered by institutions differing in Leapfrog Safety grades (Table 1).

A critical part of this survey was evaluating the ERS and looking at its utilization, assessment and processing. The vast majority of institutions (96%) reported that they utilize an ERS. Most institutions reported that nursing staff (96%), residents (94%), physicians (92%) and non-healthcare workers (76%) had access to the ERS, but only 69% of medical students could report events. When DIOs were asked about the amount of time it takes to report an event within the ERS, half reported that it took one to five minutes, while a third reported it took six to ten minutes (Figure 3A). DIOs indicated that reports were resolved in <1 week (26%) or in 1-2 weeks (43%) (Figure 3B).

While most residents and fellows may have had access to the ERS, very few were reporting either safety events or near misses, according to the DIOs surveyed. For any given month, 77% of DIOs said trainees reported 0-10 safety events, 17% reported 11-30 events and 6% indicated 31-60 events; the number of near misses reported were 0-10 (90%) and 11-30 (10%). When asked to speculate on the reasons for the lack of reporting, “Too busy” (73%), “Incident seemed trivial” (63%), “Lack of time” (61%) and “Forgot to report” (59%) were the 4 most common responses (Figure 4)

Another important aspect of this survey was evaluating how the reports within the ERS were processed. It was determined that 98% of institutions processed their reports within the ERS in-house versus an outside agency. Institutions utilized medical record specialists, QI/PS chair/manager or director, risk management staff and even a GME team as the different types of in-house initial processing of events reported within the ERS. After the initial processing of reports, this survey found that there is no one uniform person who reviews these reports nationally. Reports were found to be reviewed by several people ranging from Program Evaluation Committee (19%), Program Directors (38%), Department Chair (33%), Chief Nursing Officer (56%), and Chief Medical Officer (58%). The survey found that 33% of institutions’ reports were reviewed by someone else not already previously identified. Some of these were DIOs, GME medical administration, stakeholders, and Chief Safety Officers. This survey also identified that 67% of institutions reported that GME receives all ERS reports regarding residents, fellows, and medical students.

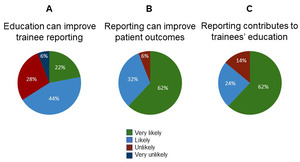

Providing education to improve PS through utilization of the ERS was reported by most DIOs. The vast majority of DIOs thought ERS reporting could very likely (61%) or likely (33%) improve patient outcomes. However, although the majority of DIOs indicated that having residents and fellows report events in the ERS very likely (61%) or likely (24%) contributed to their education, fewer DIOs reported that trainee education alone was very likely (22%) or likely (43%) to improve safety event reporting (Figure 5).

DISCUSSION

Our study found that the institutions, as reported by responding DIOs, were equally split between those that had <10 GME programs (n=25) and those that had 10 or more GME programs (n=25). This survey identified that the most common training methods utilized were online modules, feedback education, communication education, and lectures. It is important to note that one of the least common training methods utilized was ERS education. A 2020 review by Aaron et al. identified 68 articles describing the most commonly used strategies to increase the use of the ERS. Of note, of the five strategies used, a combination of three appeared to generate the most sustained improvements in reporting: 1) behavior modeling (and training) provided education to increase knowledge and/or by new technologies to increase performance of desired behaviors; 2) messaging in various forms (document, emails, in meetings) was used to promote and reinforce ERS behaviors; and surveys (and interviews) were used to promote resources and allowed feedback from trainees about barriers to ERS use, such as culture.10 Future research will be important to assess the sustainability of such strategies.

Our survey found that the majority of institutions (90%) had a QI/PS institutional committee but only about a third also had a GME-specific QI/PS committee. Trainees may be more receptive to QI/PS training and better understand their role in QI and PS activities when this information is delivered by a GME-specific QI/PS committee. Continuous education, with an emphasis on an environment of safety, should be the goal of any medical education training. However, despite the call to have the trainees use the ERS, the voluntary aspect of reporting still needs to be maintained, as indicated by the important statement made in the paper To Error is Human: Building a safer health system, “Health care organizations should be encouraged to participate in voluntary reporting systems as an important component of their patient safety programs.”11

This survey determined that 96% of responding institutions utilized some type of ERS. We asked DIOs to report on how much time it took to fill out an event report in the ERS - 33% of institutions reported it took between 6 and 10 minutes with the remaining 17% stating it took >10 minutes. This addresses one of the common barriers reported as to why an event is not reported via the ERS - 39% of institutions reported that the form was too long. Although the DIOs suggested this as one of many reasons trainees do not report events, half the DIOs reported the amount of time it took to complete a form through the ERS was 1-5 minutes. Thus, some of the other barriers selected by the DIOs were likely areas that could be evaluated more closely to improve reporting via the ERS. Many barriers, such as, “The incident seemed to be trivial” or “Not sure who is supposed to make report” could be improved with proper education to each trainee as we try to integrate QI and PS more effectively and efficiently. One study found that almost half of the reports via ERS were submitted from nursing staff, while less than 2% of reports were from trainees and attendings.12 This statistic shows that education is warranted to help increase the number of physicians using the ERS.

Our survey also evaluated the number of safety events and near misses reported by institutions versus by residents and fellows, and results showed that residents/fellows reported very few safety events and near misses. This would be consistent with data from several studies in which different strategies have been implemented to increase training reporting because the reporting level has been deemed too low.13–16 Interestingly enough, it appeared that institutions overall were more likely to report safety events than near misses. It brings up the question - is this once again a lack of education in how to report, vs. lack of understanding of what is considered a near miss or could this be that near misses occur less often than overall safety events. Our survey found that approximately ⅔ of institutions believed that by providing education to residents/fellows regarding the ERS, they could improve the percent of trainees that utilized the ERS. Increased ERS reporting by trainees may be very important to healthcare institutions, which may be missing out on identifying specific system vulnerabilities, given the trainees’ unique perspectives versus other healthcare workers.17

Lastly, the main limitation of our study was our suboptimal survey response rate. Only 51 DIOs responded out of an initial 650 institutions that were sent the survey. The generalizability of the results was hindered by the survey rate and the lack of a survey question asking about geographic location within the US, but the institutional sizes were wide ranging. It is possible that by including the Leapfrog Hospital Safety Grade within the study, we decreased our response rate as hospitals did not know or did not want to express their safety grade particularly when they received a low grade. Sending the survey via email might also have been a factor as the email address may not have been current, the DIO may have been replaced, and/or the email may have been overlooked. Furthermore, the 6-month interval between email reminders was too long, which did not permit an accurate assessment of the QI and PS education at a single point in time, especially given the everchanging environment due to the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic.

CONCLUSIONS

The majority of DIOs that responded to the survey had institutions with ≥4 GME programs (n=37), offered <10 residency programs (n=32), and 98% (n=49) taught medical students. The majority of institutions provided QI (n=44) and/or PS (n=47) training. The most common QI/PS training methods utilized by programs were online modules, feedback education, communication education and lectures, although one of the less common methods was education on the ERS. Importantly, this survey identified that approximately ⅔ of institutions believed that by providing education on the ERS, we would improve the resident/fellow participation in event reporting as well as contribute to their total education.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Formal Analysis: Megan Atkins (Supporting), Silvy Akrawe (Supporting), Jeffrey C Flynn (Lead). Writing – original draft: Megan Atkins (Equal), Silvy Akrawe (Equal). Investigation: Silvy Akrawe (Lead). Data curation: Silvy Akrawe (Lead), Jeffrey C Flynn (Supporting). Writing – review & editing: Jeffrey C Flynn (Supporting), Abdulghani Sankari (Supporting), Vijay K Mittal (Lead). Visualization: Jeffrey C Flynn (Lead). Conceptualization: Abdulghani Sankari (Supporting), Vijay K Mittal (Lead). Methodology: Vijay K Mittal (Lead). Supervision: Vijay K Mittal (Lead). Project administration: Vijay K Mittal (Lead).

CORRESPONDING AUTHOR

Vijay K. Mittal, MD

Associate Designated Institutional Official/Director

Department of Medical Education

Ascension Providence Hospital

16001 West 9 Mile Rd

Southfield, MI 48075

Ph: 248-849-5525

Fax: 248-849-5323

Email: Vijay.mittal@ascension.org

__healthcare_workers.png)

_and_graduate_medical_education_depa.png)

_and_resolve_a_report.png)

__healthcare_workers.png)

_and_graduate_medical_education_depa.png)

_and_resolve_a_report.png)